The third floor of the Cape Ann Museum is home to a gallery featuring a small but always-rotating selection of linoleum prints culled from their completist’s collection of linoleum prints by the Folly Cove Designers. A regional collective named for the tiny Gloucester neighborhood in which they operated, the group was spearheaded by San Francisco Art Institute graduate and North Shore transplant Virginia Lee Burton. More than forty artist members (roughly twelve at any given time) moved through the group over the course of its thirty-one-year duration from 1938 to 1969. Burton, arguably the most skilled of the lot (and always the most prominently featured within the museum’s space), remained the only constant.

Best known for her children’s books, including 1942’s Caldecott-awarded The Little House, Burton contrived the stylistic template for (primarily female) artists amid a growing art hub in a city whose prime industry was granite and fishing. While Gloucester’s unspoiled beaches, imperious architecture, and imposing quarries had attracted such luminaries as Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, and Milton Avery, one rarely sees Folly Cove prints outside Cape Ann today.

Virginia Lee Demetrios (1909–1968), Folly Cove Designers Diploma, undated. Ink on linen. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum.

One did not have to be a professional artist to fit Burton’s criteria for membership, the only requirement being a show of sufficient promise and a commitment to the creation of one design per year. Although she rejected the title of president in the interest of solidarity and equality, Burton maintained leadership in the juried process for the acceptance of new members and remained the arbiter as to whether a design was ready to be carved or needed adjustments. She was also strict in her stipulation that the work conform to a collective (if not uniform) stylistic approach: light-hearted, decorative design-cum-narratives best reflected in her early twenty-five-panel masterpiece, The Making of a Block Print (date unknown). In a sequential presentation indicative of a subtle (almost certainly unintentional) overlap with the concomitant rise of comic books’ golden age, a young woman sedulously moves through cogitation, inspiration, carving, inking, and printing to finally present the finished piece to the viewer.

Linoleum was first used as a printmaking substrate by turn-of-the-century Expressionists in Germany and Vienna roughly thirty years after it was patented as flooring. The first half of the twentieth century saw notable examples, including the London-based Vorticism movement (which employed traditional Japanese woodblock registration) and Picasso’s reductive format, both of which bolstered the medium’s versatility.

Folly Cove designs started with drawings that were transferred onto linoleum using a variety of techniques, and blocks were inked with a standard hard rubber Speedball brayer charged with a mixture of oil paint and commercial ink. (The museum’s gallery devotes equal space to the blocks and the prints.) Inspired, guerilla printing saw the inked blocks placed face down on fabric and exhaustingly jumped on as elucidated in the above-mentioned Making of a Block Print. While the acquisition of a colossal, lever-operated book press—a fixture within the museum’s displays—assured for even prints, a similar level of stamina was required to operate the intimidating hand crank.

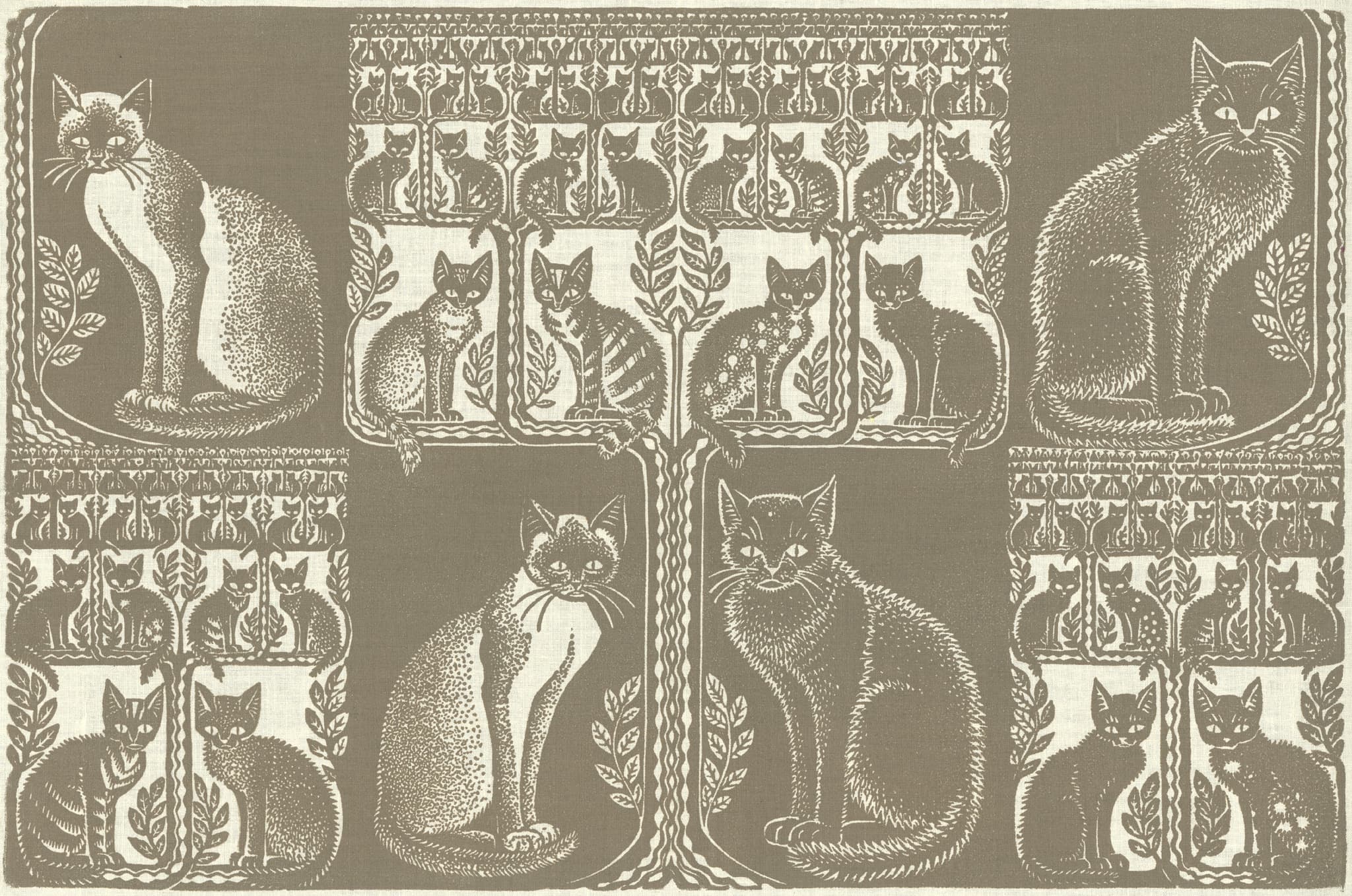

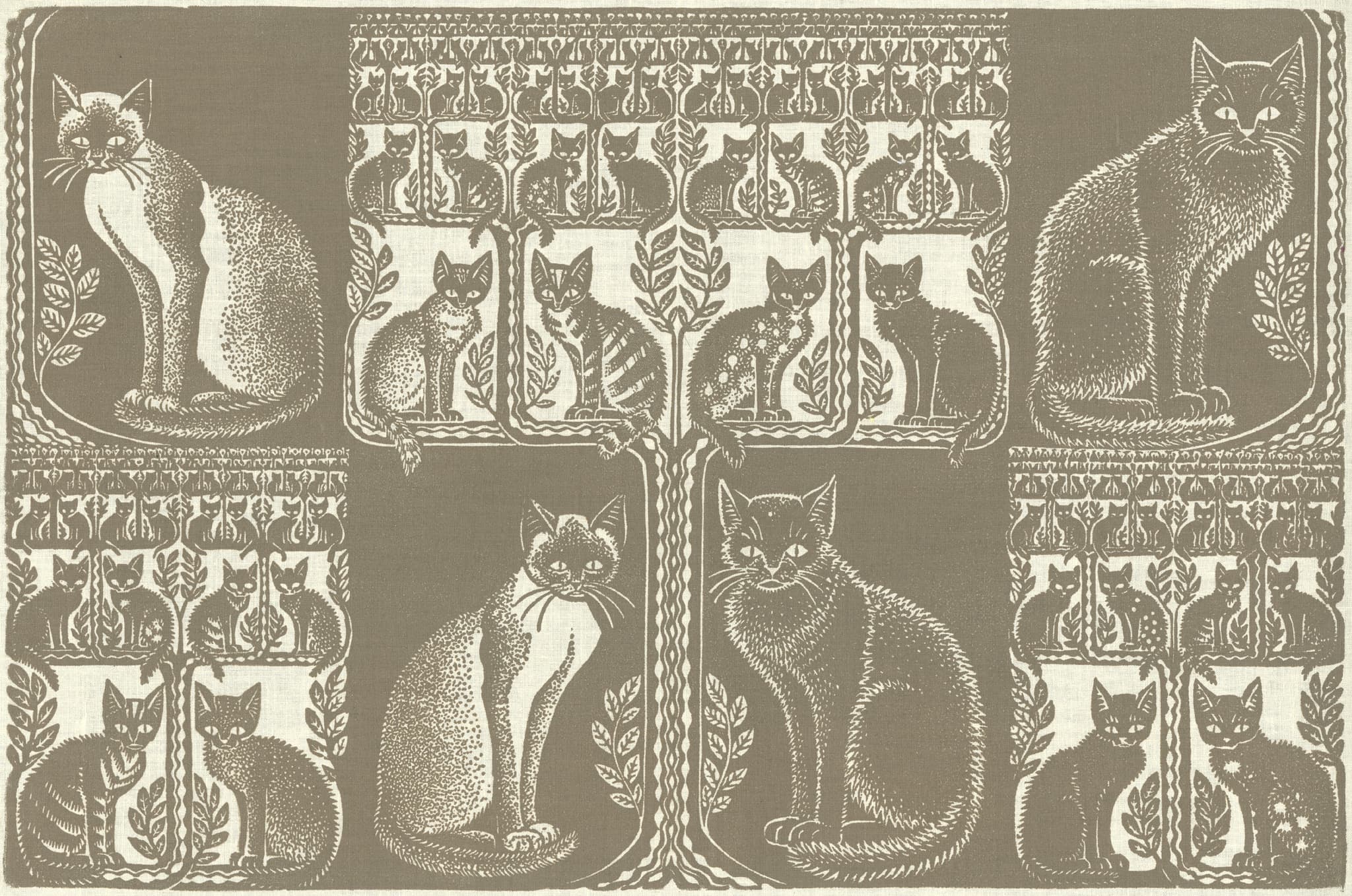

Virginia Lee Demetrios (1909–1968), Zaidee and Her Kittens, undated. Ink on linen. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum.

The local so-called battleship linoleum used by the Folly Cove Designers held a capacity for detail akin to wood engraving—and detail is at the marrow of the work’s foundation. Consider Burton’s 1954 print Zaidee and Her Kittens, in which two cats—one black, as delineated by whisps of small, jagged gouges by way of outline; one a stippled gray—sit in the upper corners and bottom center of the fabric. The stylized tree that runs through the center bears two more sets of smaller cats from which spring yet another four pairs. And it doesn’t stop there: each set of smaller cats spawn an additional clowder of sixteen, above which yet another thirty appear (the latter now more akin to a decorative border). In all, no less than 124 felines are featured. Zaidee proved to be Burton’s most popular print and was offered as a free placemat to incentivize potential adopters from one of the cat’s countless litters.

Mary Maletskos (1918–1993), Peony, 1964. Ink on linen. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum.

The use of fabric (there are no extant examples of Folly Cove prints made on paper) underscored Burton’s assertion of craft as fine art as evinced in the prints’ functional use as table linens and clothing. As New York expanded its role as center of the international art world, the Folly Cove Designers seized on their own brand of modernism through what was soon coveted as textile design. While most art being created—and purchased—remained out of the realm of the avant–garde, such homey charm made a deep impression in New York at a time when critic Clement Greenberg wrote that “part of the pity of modernism” is that “decoration is asked to be ‘merely’ pleasing.”

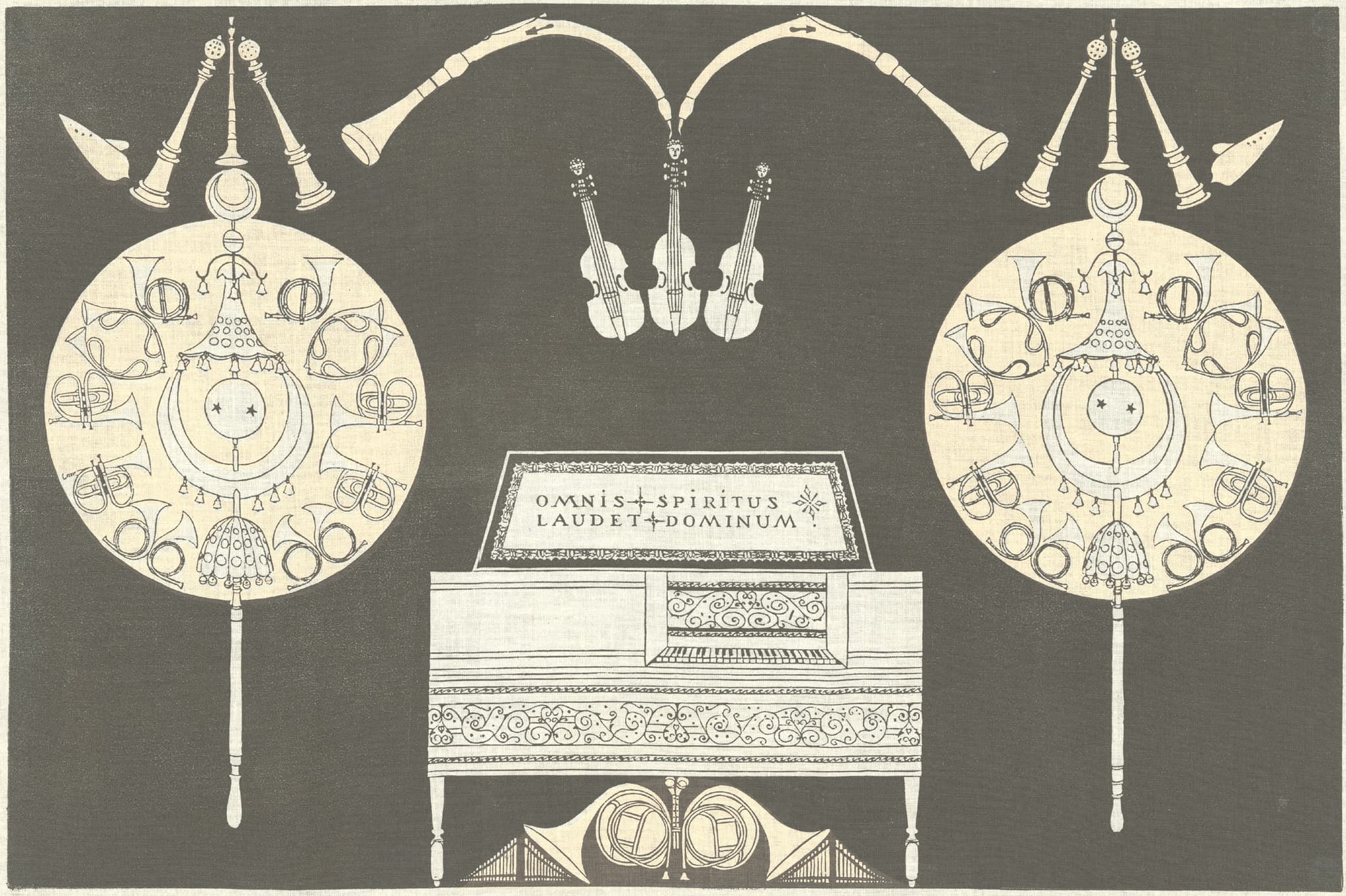

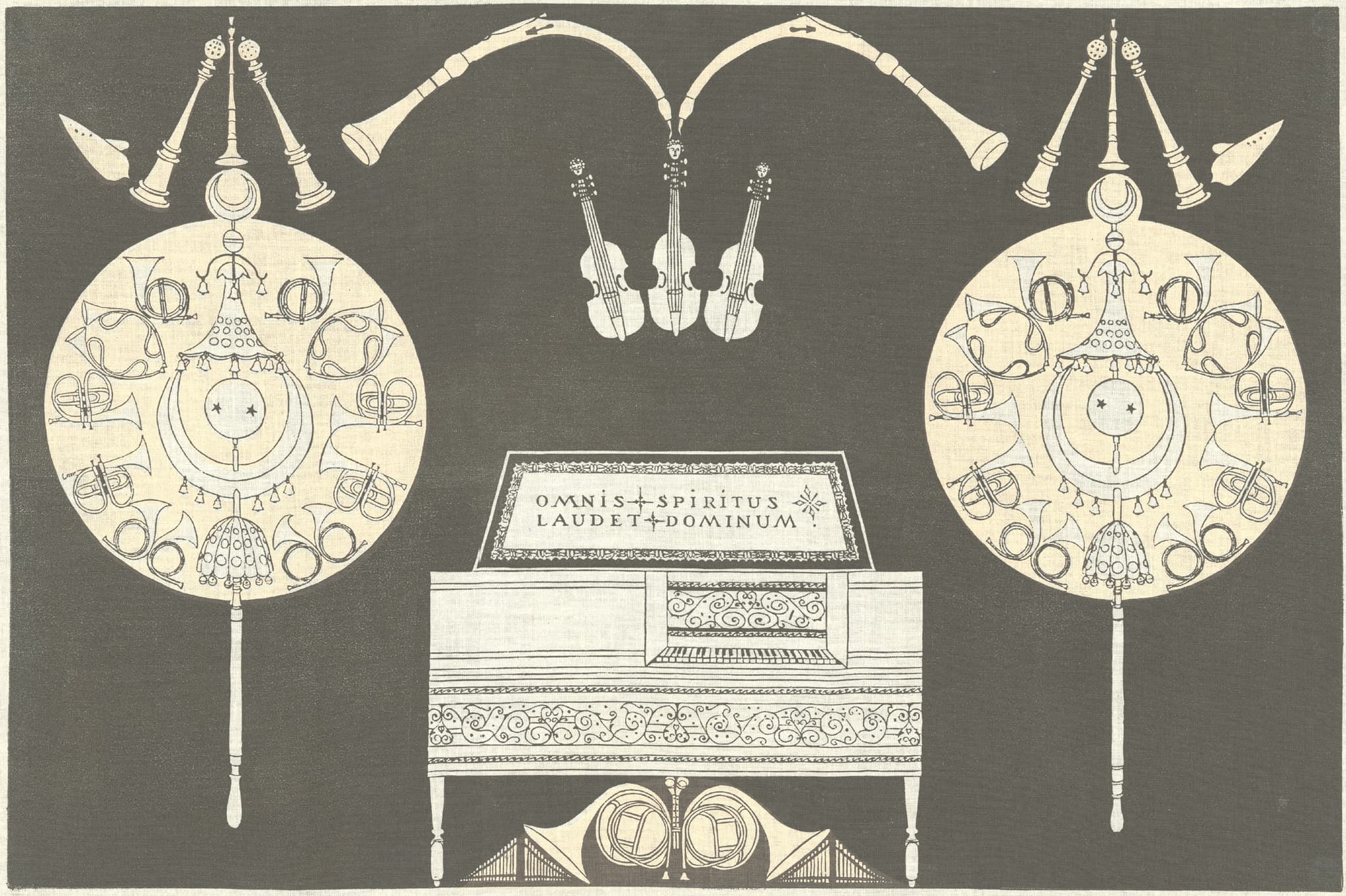

Aino Clarke (1914–1995), Instrumenti Antiqua, 1959. Ink on linen. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum.

The city’s artists and dealers who summered in Cape Ann regularly attended the annual exhibitions held in Burton’s converted barn. “Everybody came,” recalled member Aino Clarke, who described the openings as “joyous events” followed by the awarding of diplomas to new members and a lobster bake. Square dances followed, as did “Finnish Hops,” as depicted in Lee Natti’s swirling narrative print wherein no less than eight dress patterns appear on barefoot female partners in wildly gyrating pigtails.

Ultimately, it was major department stores—a different breed of the New York cognoscenti—that launched the group to national fame. Lord & Taylor proved both instrumental in helping them navigate the male-dominated field of retail and fast-tracked a 1945 Life magazine feature. By the mid-forties, retailers had become the summer exhibitions’ primary attendees as members turned to pattern-oriented imagery capable of creating large, seamless swathes of fabric for commercial use through repeated printings.

Folly Cove Designer Margaret Norton demonstrating the printing process, undated. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum.

Margaret Norton, one of Burton’s most dedicated students, was among the most skilled members when it came to detail paired with unadulterated design, and while her imagery was suited to reprinting for the creation of wallpaper and functional decor, her circular, doily-like, homespun mandalas are considerably more effective when displayed as solo wall hangings.

In 1948, the Folly Cove Designers trademarked their name to prevent retailers from tweaking their designs. Though prices remained modest, the group derived significant income through the sheer volume of sales. As demand grew evermore difficult to fulfill, the commercial world came to clash with Burton’s fidelity to the work’s original intent of humble purity, so when textile giant William Skinner & Sons asked permission to alter designs to accommodate contemporary fashion trends, she refused. As disagreements arose with members who remained amenable to compromise in the interest of greater income, Burton established a Folly Cove retail outlet in the barn alongside the exhibition space.

Burton’s unfinished instructional book, Design and How! (primarily directed toward housewives—a group to whom creative pursuits were often discouraged), served as a manifestation of Harold Rosenberg’s contemporaneous assertion that “an artist is a person who has invented an artist.” Burton’s enjoinment that her artist-students “Never be satisfied” exemplifies the same tough love that pushed the Folly Cove Designers to new levels of mind-bending detail rarely seen in relief printmaking: deceptive simplicity in which gauged marks collude in step to create psychedelic tide pools that sooth, stoke, and confound the eyes in a joyously disorienting admixture of craft and fine art.