At Harvard Art Museums, “Edvard Munch: Technically Speaking” sets itself apart from the surplus of Munch exhibitions that focus on the artist’s anxiety-inducing paintings and prints charged with emotional turbulence. Instead, it turns to the manifold methods applied to his prints and—to a lesser extent—his paintings. With painstaking clarity, the exhibition’s comprehensive wall didactics elucidate medium, methodology, and materials employed by an artist who remains both the progenitor of European Expressionism and, arguably, history’s most innovative printmaker eighty years after his death.

Munch came of age amid a larger cultural embrace of foreboding disquietude and a pronounced climate of isolation. In 1869, the American psychiatrist George M. Beard coined the term “neurasthenia” to denote the social disconnect, nervous exhaustion, and chronic fatigue that emerged amid the proximity of urban overpopulation in the wake of the Industrial Revolution. Themes of instability and the dissolution of interpersonal connection became a growing motif in contemporaneous art and literature, comprising the primary philosophy behind the Kristiania (now Oslo) bohemia (led by the anarchist agitator Hans Henrik Jæger) of which Munch was an active participant. It was an epidemic the artist was quick to exploit, converging as it did with his own alcoholism and unsound temperament: “Without anxiety and illness, I would have been like a ship without a rudder.”1

(both) Edvard Munch, Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones), 1899, printed c. 1917. Installation view, “Edvard Munch: Technically Speaking,” on view March 7–July 27, 2025, at the Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA. Photos © President and Fellows of Harvard College. Courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums.

The exhibition’s first room serves as a vast window to the exhibition and features its most prominent image, Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones). A man and a woman, their backs turned to the viewer as they contemplate a shoreline, presents an elegiac icon of disconnect amid human proximity presented here in two oils, five woodcuts, and one etching. As was Munch’s habit, the scene was recreated countless times over the course of more than forty years in canvas and print. The earliest extant version, dated 1906 (the 1892 original having been destroyed in transit from Oslo to Berlin), reveals the confidence with which Munch applied his signature combination of scratched, reworked impastos that radiate chilling unrest. Thinned, layered brushstrokes that occasionally creep down the canvas bolster the wider cultural break with Neo-Romanticism and Symbolism on which the artist was weaned. Loath to part with his paintings (Munch referred to them as “my children”), numerous versions evince his compulsion to reproduce them upon their sale. A second painted version of The Lonely Ones, completed in 1935 (forty-three years after the creation of the original), further highlights the obsessive urgency that spurred his self-assured application of paint. “He couldn’t let it go,” co-curator Elizabeth M. Rudy says of the image that he continued to explore throughout his life, notably in print form.

By his own estimation (and confirmed by Gerd Woll’s herculean 2001 catalogue raisonné of his graphic work), Munch produced roughly 30,000 impressions within the fifty-year span from 1894 until the year of his death in 1944. On loan from the Munch Museum in Oslo are six original woodblocks, one lithographic stone, and the copper plate for The Lonely Ones. The artist’s penchant for reprinting from these matrices decades after their initial run has confounded historians’ and catalogers’ attempts at accurate dating since the artist’s lifetime. Munch was not known for carefully dating his work, or adhering to conventional archival practices, evinced by the casual, even careless manner with which he treated them (thousands of prints lay carelessly strewn about his many residences). A late-life mania for editing his work, such as changing dates when hand-coloring decades-old prints, also continues to stymie historians’ and critics’ posthumous attempts at chronology. However, studies of the paper he used as well as the wear and tear of his blocks and plates have proven helpful in deducing where the work was printed and to pinpoint rough timelines, with a prefusion of examples on view in “Technically Speaking.” While he made constant attempts at a semblance of order, the artist wrote that “the worst thing about selling prints is hunting them out.”2 Most of Munch’s print sales were undertaken by the artist himself in the decade between 1910 and 1920 after he’d permanently settled in Norway, where he installed a lithography press in one of the bedrooms and an etching press in the kitchen.

Edvard Munch, Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones), 1894. Etching and drypoint printed in black ink on white wove paper. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, The Philip and Lynn Straus Collection, 2023.559. Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College. Courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums.

Edvard Munch, Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones), 1894. Etching and drypoint printed in black ink on white wove paper. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, The Philip and Lynn Straus Collection, 2023.559. Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College. Courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums.

First exhibited in Berlin in 1892, Munch’s graphic work was a financial flop. His income derived almost solely from the admission fees that, with entrepreneurial moxie, he had established upon his first solo exhibit. Although institutions and private collectors were keen to acquire his paintings, his graphic work was off-putting in its selective inking, woodcuts from blocks that had cracked under the pressure of the press, and experimental registration. Yet the artist remained inflexible as to pricing and strict in his definition of authenticity in a medium that was often farmed out to professional printers. Writing that “the artist is just the midwife” in the production of prints, he further insisted that “impressions printed without the presence of the artist are not original.”3 In 1907, he became the sole arbiter of his prints, burdening himself with yet another relentless obsession to revise, reorder, and reclaim.

In the gallery space, an etched version of The Lonely Ones (likely his first print, further suggesting the importance he ascribed to the image) is executed with the same self-assuredness with which he approached all mediums. To its right, a row of five woodcut versions moves seamlessly from deep, aggressive blue-black coats on sturdy European rag paper to mellow, midnight sun pastels absorbed by thinner Japanese sheets. (A sampling of papers offers further insight into Munch’s attention to the ways in which ink is either absorbed by or lays on top of the most delicate mulberry paper, sturdy laid linens, or acid-ridden board.)

The artist’s contrivance of cutting his woodblocks with a fretsaw to be inked separately and reassembled prior to printing assured for infinite color variations, while the exploitation of wood grain adds organic fragility and concrete evidence of the print’s substrate. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the woodcut versions of The Kiss. Originally painted in 1892, Munch revisited the image in print over the course of decades. In the exhibition’s three featured versions, the original background curtains and windows are absent to devote sole attention to the embracing couple as they merge and morph into a single form over multiple backgrounds in varied grains.

Installation view, “Edvard Munch: Technically Speaking,” on view March 7–July 27, 2025, at the Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA. Photos © President and Fellows of Harvard College. Courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums.

The Kristiania bohemia’s embrace of emotional strife included manifestos exhorting free love as a means of railing against bourgeois convention, an experiment that failed on all counts as it fast devolved to jealous obsession and tormenting love triangles of which Munch was an unwitting casualty. The climate of misogyny, in which women were depicted as sexual predators and syphilitic liabilities is perhaps best exemplified here in the color lithograph Madonna (1895), in which a woman lies bare as though making love to the viewer. Yet her sunken eyes and thin mouth convey not love but disease, reinforced by the spermatozoa that run through an orange border where a withered, sickly infant cowers in the lower left corner amid the curse of deliverance.

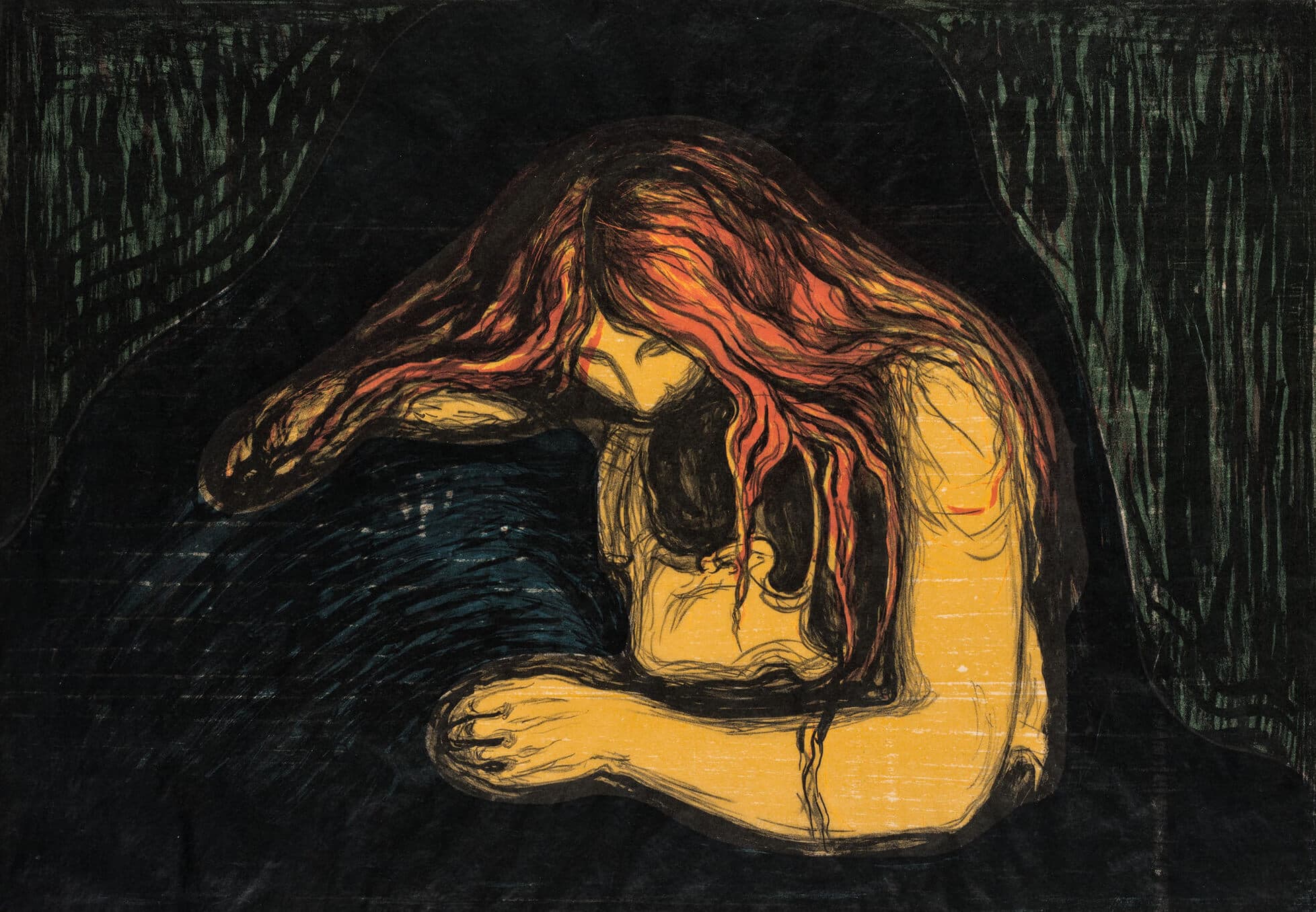

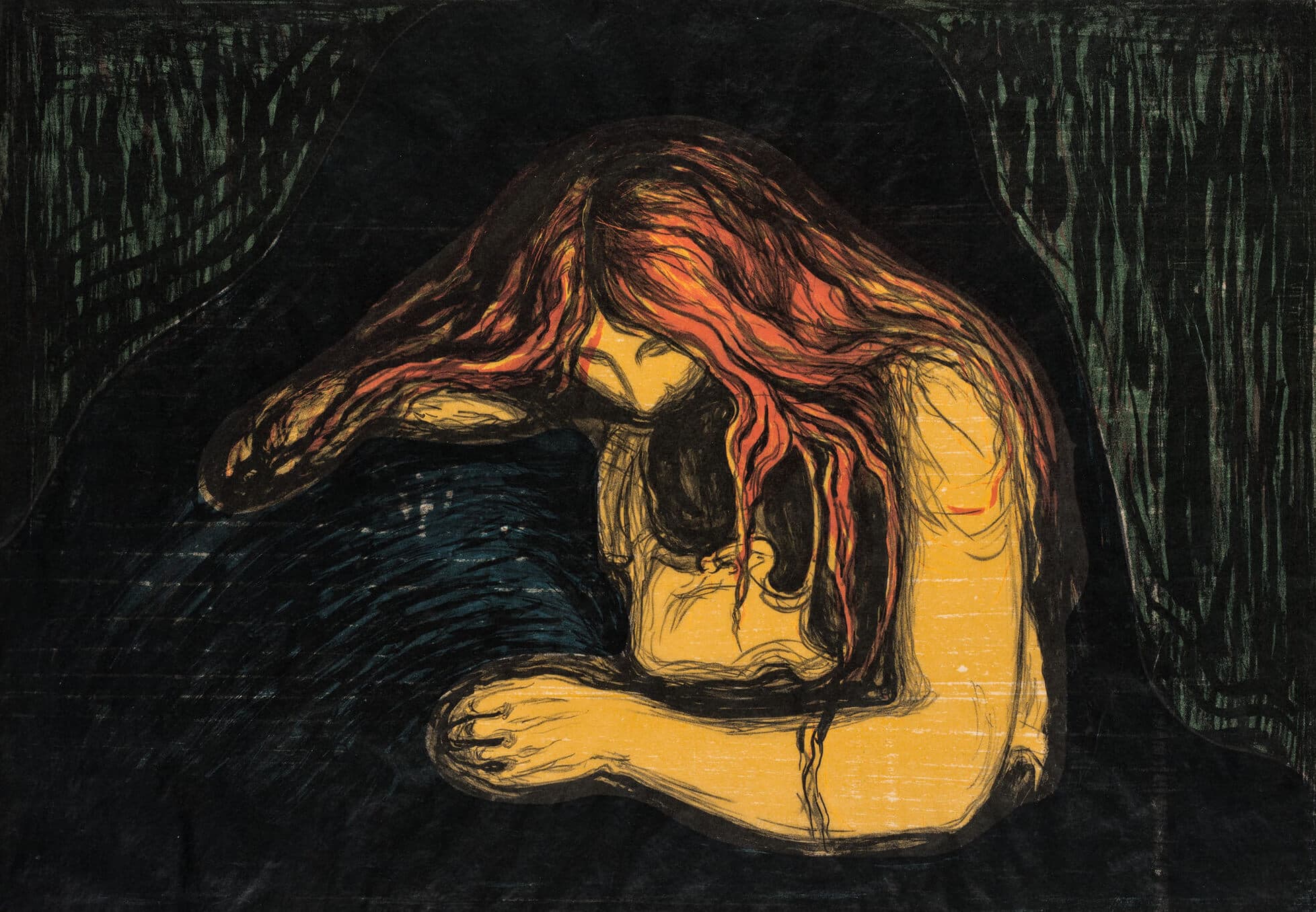

Three versions of the woodcut lithograph Vampire (1895–1902) further elucidate the era’s dreaded awe of women as sexual predators. Originally titled Love and Pain, Munch changed the title to Vampire at a friend’s suggestion to capitalize on his terror of passing the seeds of illness (he lost both his mother and a sister to tuberculosis as a boy and was frequently confined to his bed) and madness (evident in his father’s unhinged religious mania and another sister’s slow descent into schizophrenia) to successive generations. The lithograph’s pitch-black tusche serves as a key block over which woodcut—again sawed to separate colors—adds tone and atmosphere sustained by the omnipresent grain’s disquieting texture.

Edvard Munch, Norwegian (Loiten, Norway 1863–1944 Ekely, Norway), Vampire II, 1895. Lithograph printed in black ink on heavy cream wove paper, mounted by the artist on coarse brown paper, 14 ¾ × 21 7/16 inches. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum. Purchase through the generosity of Lynn and Philip A. Straus, Class of 1937. Courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums.

The relative scarcity of paintings, dispersed throughout the exhibition among rarely seen prints, poses no threat to the show’s cohesion. Instead, its strength lies in the rich array of print techniques—many of which remain unfamiliar to the casual viewer (Harvard owns one of the largest collections of Munch’s graphics in the country.) With the exception of The Lonely Ones, most of the canvases have rarely been shown outside the artist’s homeland, offering a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for viewers.

The second most recognizable canvas is a later version of the 1900 landscape Train Smoke. A stimulation of frenetic zig zags from a charged but worn brush that both adds paint and subtracts via deep scratches enlivens a composition that largely wilts when recalling the original from ten years prior. Yet in keeping with the exhibition’s overarching theme, emphasis does not necessarily rest with the images themselves so much as their execution, particularly the application of paint. While some of the work is revealed to contain large areas and figures that have been painted over, the majority feature a broad variety of mark-making wherein paint is manipulated in strokes that snake in thick ropes or spread like stains as though absorbed by the canvas. In many instances, it is often impossible to determine whether what appears to be “unfinished” paintings indicate intent or abandonment.

Edvard Munch, Norwegian (Loiten, Norway 1863–1944 Ekely, Norway), Train Smoke, 1910. Oil on canvas, 36 ⅛ x 45 ⅞ inches. Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, The Philip and Lynn Straus Collection. Courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums.

As Munch reached his forties following a prolonged stay at a Copenhagen clinic for his alcoholism and frayed nerves, he turned largely to landscapes and portraits, the former almost wholly comprising the exhibition’s sampling of paintings. The diminutive, knockout canvas From Kragerø (1929) presents a scene that, like so many of Munch’s late landscapes, feels at once rushed and wholly comprehensive, drawing the viewer in through rocks set in one-point perspective to reveal a hill of houses and the artist’s signature trees, trunks rising from the earth to culminate in curt wisps encapsulated in ovular delineation. The same method, employed in Winter Night (1900), further clarifies his layering of paint despite muddled trees and hedges that obviate the luminous effects of Munch’s signature, nighttime greens.

“Technically Speaking” can easily stand alone as a heady grouping of the artist’s prints and a handful of fresh canvases that, despite their unevenness in quality, are thoroughly suited to an examination of the artist’s working methods. Enthusiasts inundated by Munch exhibitions that stress a nervous temperament and zeitgeist of isolation and anxiety will revisit familiar prints in a new light, their technical perplexities resolved. In its collaboration between curators and conservation experts, the exhibition is an expository thrill for admirers of the artist and those willing to take a deep dive into Munch’s innovative, manifold processes.

1 Patricia Berman, Reinhold Heller, and Elizabeth Prelinger, Edvard Munch: The Modern Life of the Soul, (New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 2006), 38

2 Gerd Woll, Edvard Munch: The Complete Prints, (Harry N. Abrams, 2001), 10

3 Ibid., 21

“Edvard Munch: Technically Speaking” is on view through July 27, 2025, at Harvard Art Museums, 32 Quincy Street, Cambridge.