In March 2020, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) was on the brink of a big change. Four years of informal conversations between colleagues had blossomed into regular meetings with a small, committed group, and now they were ready to launch union authorization cards, allowing workers to register their support and petition for a formal vote with the National Labor Relations Board. “Unfortunately, March 2020 had other plans,” says Eve Mayberger, an assistant objects conservator at the MFA who was among the initial group campaigning to unionize.

Of course, for the museum, like the rest of the world, spring 2020 was a time of unprecedented measures and uncertainty. “A lot of people, including myself, were furloughed for about four-and-a-half months,” remembers Mayberger. And yet, instead of bringing the union drive to a halt, the lockdowns (and the museum’s response) helped to reinforce the reasons to unionize in the first place. Museum workers were isolated, and the union represented community, a way to connect with something larger than themselves. With the MFA announcing layoffs and furloughs, it became clear that most employees were going to have very little say in the emergency measures put in place. Remotely, the plans for the union continued apace.

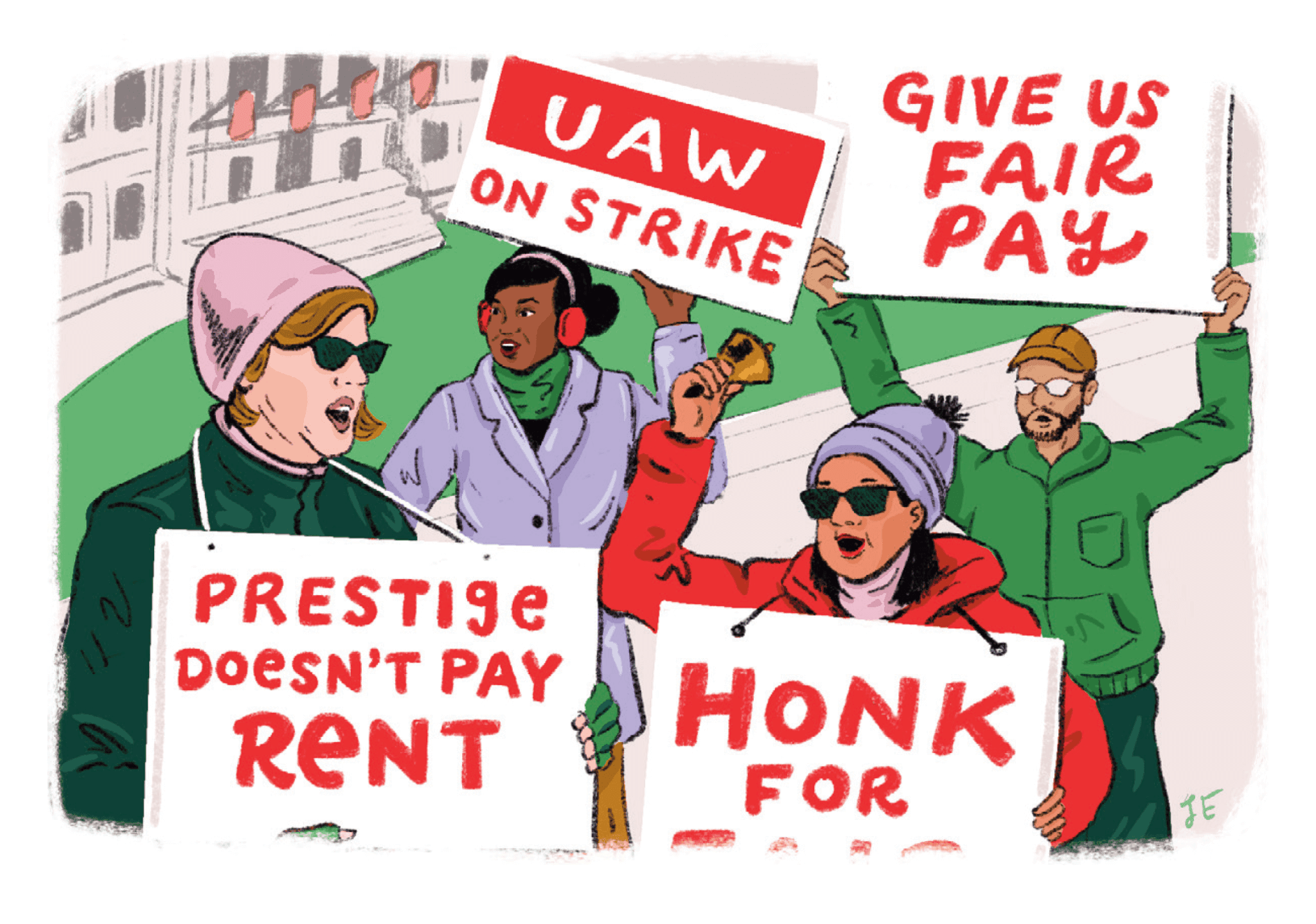

The MFA is hardly the first museum where workers have organized to demand more equitable working conditions. After all, these are institutions where leadership execs can expect to earn hundreds of thousands of dollars a year (in 2020, MFA director Matthew Teitelbaum’s salary was nearly $1 million). The past few years have seen ongoing campaigns at the Whitney, the Guggenheim, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the New Museum. Indeed, at the time of writing, MASS MoCA’s union had just held a strike to demand better working conditions. Many of these efforts have taken place with the union United Auto Workers Local 2110, which also represented the MFA workers. “It’s been very similar to what we’ve seen in the last few years, where there’s very strong impetus on people’s part to unionize,” says Maida Rosenstein, who was president of the union until recently. “Unions are winning elections by very, very strong margins,” she says, noting that more than 90 percent of the MFA workers voted to form a union.

Though it was delayed by the pandemic, the successful vote among staff finally took place electronically in November 2020. Yet in many ways this was only the start—the point at which the union would begin negotiating the contract that would cover all of its workers’ employment. “It was a struggle,” says Martina Tanga, curatorial research and interpretation associate at the museum, who joined the bargaining committee at the end of 2020. “There were plenty of things we had to give up.”

One stumbling block, apparently typical in union negotiations with museums, presented itself immediately: Who exactly was eligible to be a union member? Anyone classed as a manager is legally excluded from unionizing under the National Labor Relations Act, where managerial employees are defined as policy and decision makers who have power over other workers. Therefore, in union negotiations, Rosenstein explains, “institutions work to claim that professionals, like curators, are also excluded” in an attempt to limit the union’s power. “They were very possessive over curators in particular, and I found that to be true with other employers.” After more than six months of negotiations and hearings with the National Labor Relations Board and third-party arbitration, it was determined that curators like Martina Tanga were not a managerial class and could be a part of the union. This episode underscores one unique challenge that museum unions face in trying to map jobs within a creative field into a system that was designed for a different kind of workplace. “The American legal code is not necessarily drafted with cultural heritage employees in mind,” says Mayberger.