By the end of “Matthew Leifheit: Queer Archives”—a collaboration between the artist, his students, and professor/curator Helen Miller—the spinning magazine rack in the center of MassArt’s small Brant Gallery space stood nearly empty. It held the last copies of The Queer Voice, a newspaper produced by Leifheit’s MA/MFA students. It also held nine of Leifheit’s own photographs of archival objects, emblazoned on newsprint in striking, collectible detail. As a course, Queer Archives took students from The History Project (one of the largest independent collections of LGBTQ+ material history in the country) to Boston’s two-year-old QT Library. As an exhibition, “Queer Archives,” which was previously on view in upstate New York under the title “Gay Archive,” brings changing selections of portraits that Leifheit creates from the personal ephemera entrusted to community archives. Leifheit’s integrated arts and teaching practice inspired third-year photographer Kyndel Whiteford to interview him for Miller’s exhibition writing class; his collection struck Miller as an opportunity for the Brant Gallery’s natural next student-professor partnership. (This gallery, nurtured through the pandemic by students and faculty, exists to host participatory exhibitions.)

Online• Jan 07, 2025

Matthew Leifheit’s “Queer Archives” Finds a Temporary Home at MassArt

A collaboration between the artist and his graduate students, the exhibition bridges personal and collective queer histories, transforming ephemera into stories of identity, loss, and memory.

Review by Bessie Rubinstein

Installation view: “Matthew Leifheit: Queer Archives” on view at Brant Gallery, Massachusetts College of Art and Design from November 25 through December 13, 2024. Photo courtesy of Massachusetts College of Art and Design.

Installation view: “Matthew Leifheit: Queer Archives” on view at Brant Gallery, Massachusetts College of Art and Design from November 25 through December 13, 2024. Photo courtesy of Massachusetts College of Art and Design.

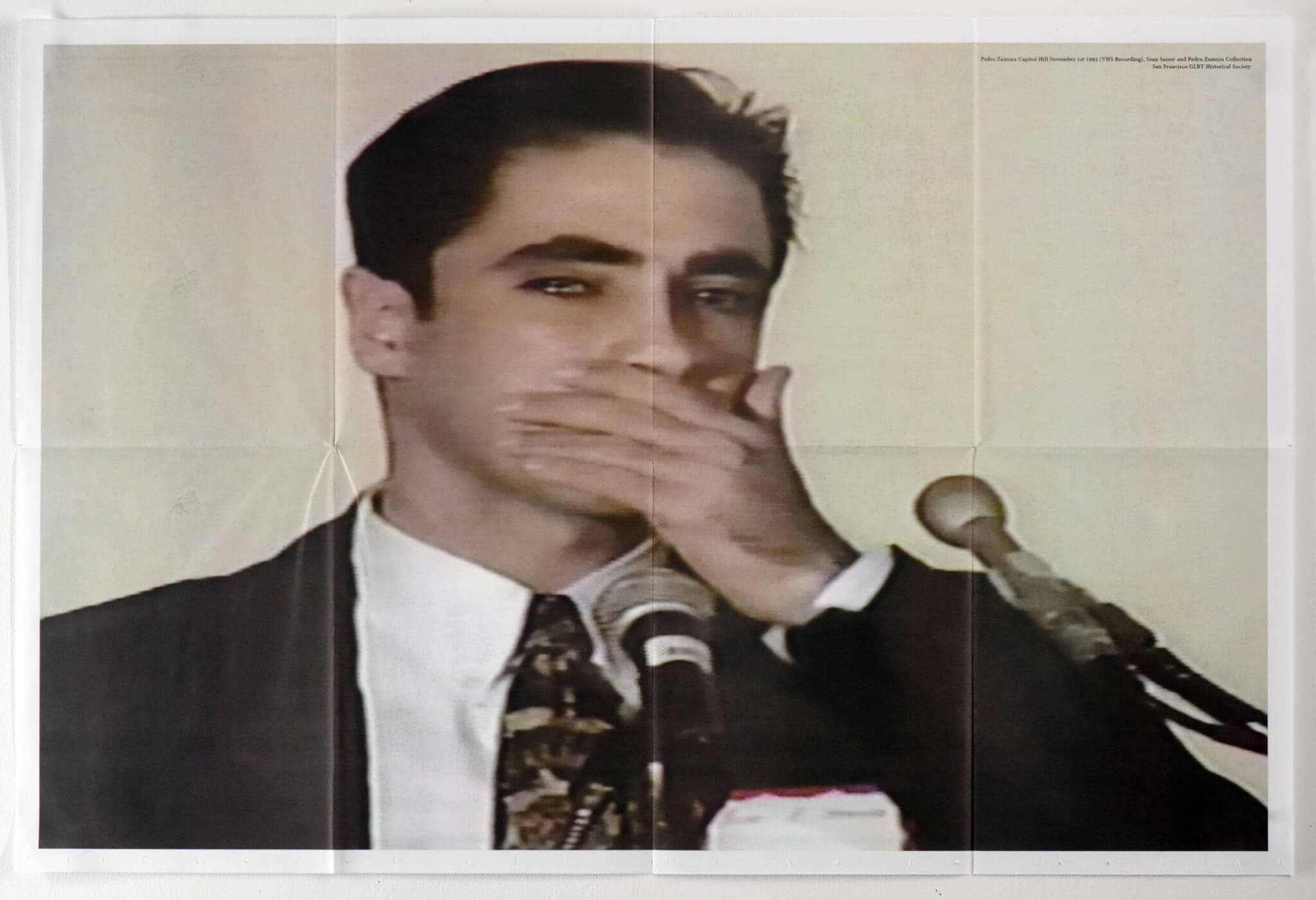

Matthew Leifheit, Pedro Zamora Capitol Hill November 1st 1993, 2024. Still image from VHS recording. GLBT Historical Society, San Francisco. Courtesy of Massachusetts College of Art and Design.

Every piece in the show struggles with the enormous implications of its title, with limited space, and with the unfortunate effect of time on memory, differently. The project’s vastness, the rabbit hole of queer history that is only lost if it hasn’t been found, attracted Leifheit, who admits he gravitates toward subjects almost too consuming to take on. One thing he can accomplish, the artist says, is to “allow these materials that are all locked away to talk to each other.” Though the rain against the gallery windows underscores the fragility of all this newspaper, which can only bear traces of a whole life, Leifheit’s portraits capture those traces with detail that pierces the fabric of time. In a still image taken from a recording from San Francisco’s GLBT Historical Society, Pedro Zamora stares frozen, cropped into a close-up so that his tears—so rare in the public appearances of television’s first celebrity with AIDS—glitter improbably from the paper. In another print, Rudolf Nureyev’s ballet shoes hang alone and pale, adorned with blood splotches like wounds, in The Watermill Center Collection of Long Island. In another print, sweat tracks seismic lines across the pink insides of Castro disco queen Sylvester’s performance costume. His sequins glimmer out of focus on the edges; it’s what’s left of his body that fills the frame.

Matthew Leifheit, Lorraine Hurdle Photo Archive, 2023. Dye sublimation print. 30 inches x 40 inches. GLBT Historical Society, San Francisco. Courtesy of Massachusetts College of Art and Design.

Here, as well as on dye-sublimation aluminum prints on one of two gallery walls, formal touches punctuate the question inherent to portraiture: “How can I contain one version of the totality of this person?” In the printing process, Leifheit actively contributes to the preservation of strangers’ histories; the aluminum, if well kept, will outlast the objects photographed. The potential immortality of Leifheit’s arrangements creates even more responsibility “to the facts of the story,” as he puts it, but also to “interpreting the materials” by arranging them. Using a large format camera he sees to the facts, preserving as much original texture in the objects of his arrangements as possible. In this way, prismatic rainbows can forever glint from the glasses and watch of Black lesbian Lorraine Hurdle, which Leifheit placed on a small quilt of photos of her life with friends, the waves she herself photographed, and pool games.

Leifheit visited his first archive at Fort Lauderdale’s Stonewall National Museum in 2021, urged by the desire to “seek out evidence of [his] cultural ancestors”—to trace a queer lineage that the homophobia, transphobia, and racism of institutional archives obscures. AIDS irreparably hastened this process, and it was in this context that many gay community groups decided to form their own bulwark against being forgotten. Queer historian Sarah Schulman writes in “The Gentrification of the Mind” that AIDS “has been bombarded by simplification since its beginning. The people who have it don’t matter. It’s their fault. It’s over now.” The diligence with which Leifheit composes his images is a balm. In one portrait of ephemera from the life of a gay man named Timothy Bass, Leifheit lays out photos of his lovers, his makeup, of him as a child, inside open boxes and booklets to remind the viewer that once, someone else kept them safe. On a CRT television, an hour-long portion of Leifheit’s The Gay Chorus (Endless Recital) (2023) plays, perpetually looping thirteen performances from gay men’s choir performances during the height of AIDS. He began digitizing these, participating in the archive, after wondering what a “group of men fearing for their lives putting on a Christmas show” looked like, and realizing no records were online. The black trails on screen, coming from the tape’s degradation, remind Leifheit of its members blowing away in the wind. This choral project now spans forty-six hours of fifty-three tapes.

Compared to the sparse detail of Leifheit’s newsprints, or the eerie carousel of his chorus videos, his course’s publication seemed to handle limited space more awkwardly. Doubtless, queer archives spill over every exhibition form they take. But next to Leifheit’s prints, The Queer Voice’s layout, which melded scattered archival photos and prints with collaged poems, QR-coded playlists, design histories, and a longform interview without context or preface, felt a little lost. Where Leifheit’s students’ project felt controlled by its limited space, his exhibition used the material it could to haunt.

“MATTHEW LEIFHEIT: Queer Archives” was on view from November 25 through December 11, 2024, at Brant Gallery, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, 621 Huntington Avenue, Boston.